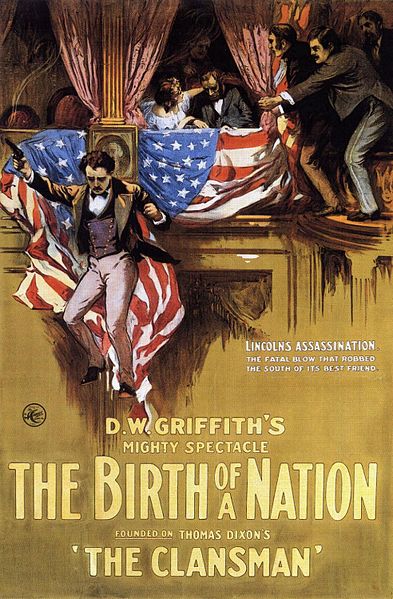

"The Birth of a Nation" (1915)

There is no question about the influence director D.W. Griffith has had on the art of filmmaking. He invented techniques that we take for granted today. And what he did not invent himself, he certainly perfected. Unfortunately, his genius was tarnished by the racist tones of “The Birth of a Nation.” I won’t address the issue of racism in “Birth of a Nation,” simply because individuals who are far more intelligent and articulate than I have

already addressed it and they have addressed it better than I could. Instead, my task with this blog is to look past the blackface and examine the film for the incredible feats it does achieve, in terms of cinematography, acting, and design.

It is difficult now to experience “The Birth of a Nation” as audiences experienced it when it premiered in 1915. Prior to its release, most films (including Griffith’s) were about 20 minutes long. “Birth” shattered that standard by clocking in at just over three hours. It was the first American epic film and the epic scope, scale, and feel of the film survive to this day. The story of the Stonemans of the North and the Camerons of the South has not lost its effectiveness or its emotion.

|

| The intertitle which appears at the beginning of the film |

D.W. Griffith & Bill Bitzer

If Griffith is the father of modern filmmaking, then Bitzer is certainly the father of modern cinematography. Bitzer had been paired with Griffith since Griffith’s directorial debut and eventually became Griffith’s regular cinematographer. Together, the two captured the Civil War in a way that, until that point, only Mathew Brady’s photographs had done. The blood of the battlefield, the affect of war on home life, the difficulty of returning to normal life after war -- all were captured with an amazing degree of accuracy and realism that hit the audience in a way it had not anticipated.

|

| This early equivalent of a crane shot illustrates the scale of the battle scenes |

The battle scenes are thrilling and haunting. Thanks to Griffith’s direction and Bitzer’s photography (as it was referred to at the time), the audience finds themselves in the middle of the battles, not merely spectators. Indeed, we ride into battle with the regiment, an effect which seems commonplace now, but which all directors ultimately owe to Griffith and Bitzer. What’s more, the effect is just as thrilling now as it was during its premiere in 1915. The same technique is used later in the film as the Ku Klux Klan rides to the rescue of the Camerons and the technique is no less effective or powerful.

|

| A powerful shot from the battle sequence |

|

| The KKK ride to the rescue of the Camerons |

Just as Bitzer and Griffith prove that they are capable of capturing large-scale action, they prove that they are more than capable of capturing the more subtle interactions between actors. When the Stoneman boys and the Cameron boys enlist to find for their respective sides, the families who were once close have suddenly become mortal enemies. This becomes painfully clear as a Stoneman and Cameron perish just inches from each other on the battlefield.

|

| Stoneman and Cameron die side by side |

Perhaps the most moving scene of the film is the homecoming scene, in which the “Little Colonel” returns home after serving for years in the war. Henry B. Walthall plays the Little Colonel, Ben Cameron, with heartbreaking realism, while the effervescent Mae Marsh plays his little sister who loves him dearly. The two are closer than any of the other family members and the excitement of seeing one another after so many years is more than either can stand.

But as the Little Colonel returns home, he is confronted with the life he left behind and the life he must lead now that the war is over. The scene is beautiful and haunting at the same time as the siblings’ joy is so quickly replaced with discomfort and uncertainty. You can watch the scene below.

Of course, Griffith and Bitzer could not have achieved such a powerful film without an incredible cast.

The Players

A commonly emphasized theme in Griffith’s films is innocence and none is more innocent, especially in “Birth,” than Mae Marsh. As the lovable Flora Cameron, Marsh beautifully embodies childhood innocence as it is forcefully faced with the dangers and evils of the world. Her energy bubbles over into every facet of her performance. Even when the Cameron household is raided and Flora, her sister and her mother seek refuge in the cellar, Marsh reminds us of how much of a child Flora really is with her nervous excitement and giggles.

She’s fearless and optimistic, a stark contrast to her sister who often seems simply catatonic. And when her brother returns from the war, she is the first to to run out and greet him. Marsh’s performance is beautiful, as she runs around trying to make herself presentable to her hero -- her big brother.

|

| Flora (Mae Marsh) puts on her finest for the return of her brother |

|

| A sweet moment from the homecoming scene between brother and sister |

The homecoming scene’s brilliance is due, in part, to Griffith and Bitzer, but it is largely due to Marsh’s performance and the performance of the Little Colonel himself, Henry B. Walthall. Ben is first the optimistic, eager young man who is ready to fight for the Confederacy, perhaps without fully understanding what would be expected of him. After a few years on the frontline, however, his spark begins to die down. By the time he returns home, he is a jaded man, having experienced death and loss firsthand. The eyes which once sparkled with life and joy become haunted upon returning home, and the pain he feels eventually turns to rage.

|

| Ben (Henry B. Walthall) and his haunted stare |

|

| Ben's pain turns to rage as Flora dies in his arms |

The intensity that Walthall exhibits in the battle sequences and the KKK ride sequences is incredible. All of his energy is invested in those scenes and that ferocity is paired with the heart-pounding cinematography of Billy Bitzer, causing even the modern audience to slide to the edge of their seats as their hearts race.

|

| Ben charges |

For Ben Cameron, few can ignite the love for life that once dwelled within him, among them are, of course, little Flora and his love, Elsie Stoneman, played by the wonderful Lillian Gish.

Gish’s career spanned more than 70 years, a feat which is nearly unfathomable. Not only was she present when the movies moved from nickelodeons to respectable theaters, she was also present for the introduction of sound, color, television and VHS tapes and VCRs. Of course, it’s not Gish’s longevity that we remember her for. Above all else, we remember her beauty and her dedication to her craft -- both of which are demonstrated in “Birth of a Nation.”

Joe Franklin described Ms. Gish as ethereal, and I think that is the perfect word to describe her. Her beauty and talent are almost not of this world and this is used to great effect in “Birth.” As Elsie, daughter of Congressman Stoneman, she has an angelic quality. Ben idolizes Elsie before he even meets her, and when he regains consciousness in the hospital Elsie is his own personal Florence Nightingale, heightening her angelic qualities.

|

| The angelic Elsie Stoneman (Lillian Gish) |

Griffith and Gish were not content to simply leave Elsie as this out-of-reach creature, however, and Gish shows her range during the second half of the film. She swiftly falls from the highs of love with Ben, to the depths of despair when she realizes that he is a member of the Klan. And the terror and hysteria she displays when she is trapped within Silas Lynch’s home brings this ethereal being down to Earth in a frightening way.

|

| Elsie realizes she is trapped in the Lynch house |

Conclusion

It’s difficult to watch “The Birth of a Nation” objectively, but if a viewer can do it, it can be an incredible movie-viewing experience. The genius present in the film cannot be denied, even if its faults tend to overshadow it.

No comments:

Post a Comment